Overload

This entry is an entirely selfish undertaking - the truth is I’m running out of time.

Or more accurately I was running out of time? Last week I was invited to give the opening Keynote for our Summer Research scholars, and the slides were due at the same time as everything else - committee meetings, exam marking, manuscript revisions, curriculum reviews… The pressure as a Keynote speaker is to be engaging, motivational, if not inspiring (cue the world’s smallest violin), but I’m not sure if I have many (if any) magic tricks left up my sleeves this year.

So…. this was my attempt at a productivity life-hack - to write my talk by narration, filming my stream of consciousness brain-storming (brain-dumping?), and using the footage to reverse-engineer some semblance of a presentation. I committed to publishing this footage as a YouTube video too, which raises the stakes! It turns out nothing makes you focus more than the risk of embarrassment on two fronts - both online and in-person if the talk wasn’t any good - so sadly this may be my new way of ensuring personal accountability in the face of looming deadlines. To triple-down on this notion, here’s the essence of my talk in blog form as well: 5 ways to develop your research skills (spread out across over the next few blogs), starting with:

Strategy I: Information Overload

The first problem we have to overcome when talking about research, is that the term research has lost a fair bit of value in the general discourse. Every person with an internet connection is doing their own “research” and falling down rabbit holes of conspiracy theories. Search engines have made it easier than ever to access hundreds of thousands of websites for the simplest key terms, so you should be intimidated by how much you need to read to gain a basic understanding of a new topic.

In research the aim is NOT to read every single thing - at least not initially. Presumably you’re a novice to the field, so you won’t have the knowledge base to assess or rank the relative importance of any one piece of information compared to the rest of it - which in this day and age is an overwhelming amount of facts and figures. Thankfully academic search engines - allow you to not only find peer-reviewed sources that have been validated by experts in that field, but also you can filter them by publication date, number of citations, authors and their collaborators. What I like to do is to find a peer-reviewed review article published in the last 2-3 years. A review is usually written by an expert in that field, which attempts to summarise all of the findings in that field. It’s like a mini-version of a textbook written by someone who in all likelihood knows everything about that topic - and you can quickly get a sense of the scope and breadth of the area. The key problems that people are trying to address, the most promising solutions that have been attempted.

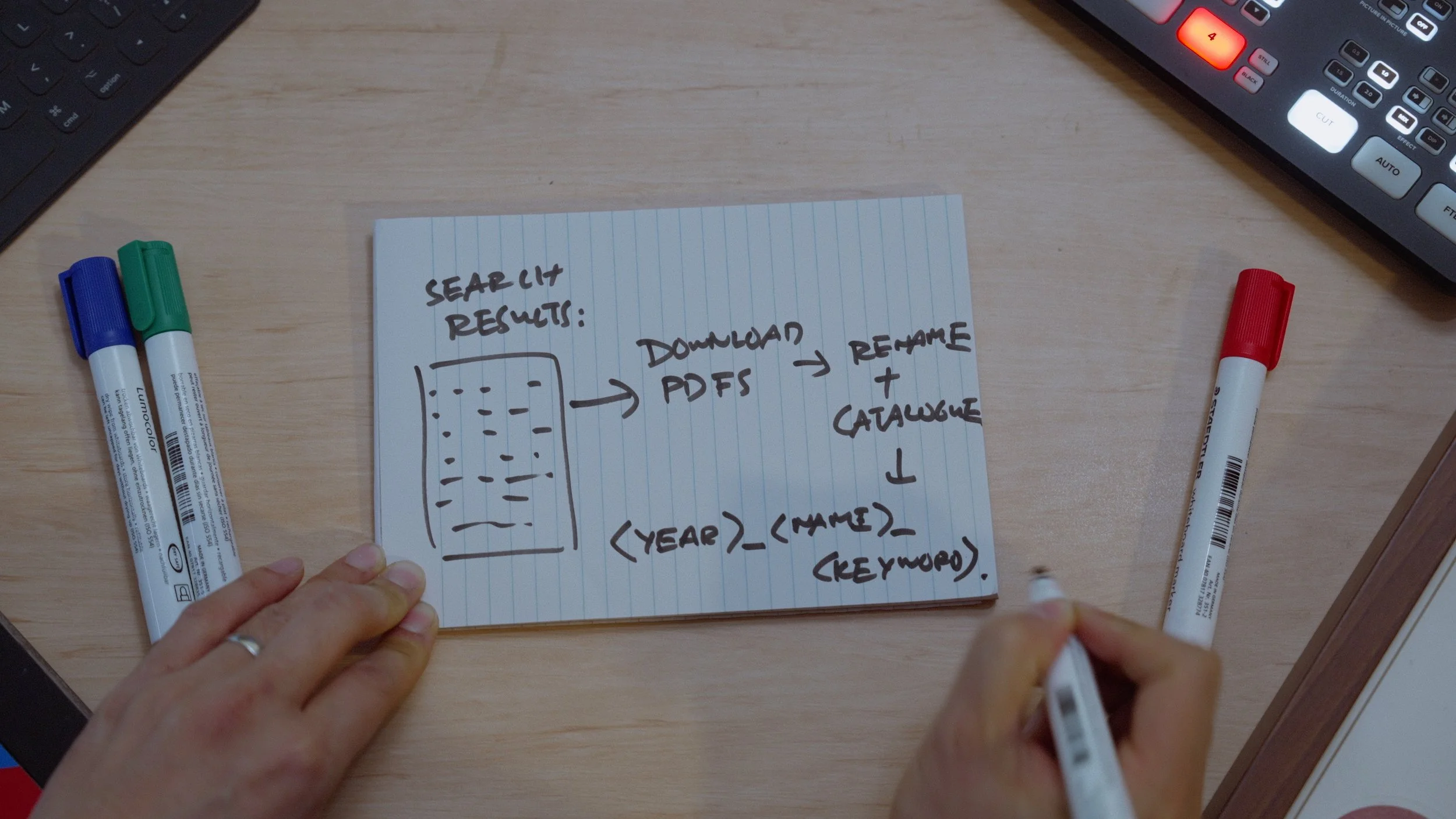

Another useful skill that will help is a coherent file management system. Super interesting I know, but by the end you will have read hundreds if not thousands of documents, and knowing where to find a specific reference on short notice needs planning. Something like Endnote can also help, but at the end of the day you need to find an obscure piece of information you’ve already read on short notice. I make my students download all the papers into PDFs, rename it by year, first author’s surname, and keyword, and that cataloguing helps a lot come crunch time - deadlines for manuscripts, or thesis submission day. Doesn’t mattter what the system actually is, but you do need a system.

If you conceptualise knowledge and understanding as trying to build a house in your mind, this first review is just setting up the foundation. How much space will the house take up, how many storeys do we need? What is supposed to go in each room? Once you know the skeletal outline of a topic, you know what you don’t know - you can be more intentional about your search strategy, and choose different combinations of keywords, and take advantage of Boolean operators - and, OR, minus sign, tilde - to filter the results to fill in specific gaps in your understanding. As you find new information, you’ll also need to decide how to process and store it. We’ve talked about note-taking strategies before, and at this level I think a mind map is most appropriate - establishing connections between the facts you’re finding out is the most important thing when grasping at the edges of a new topic, rather than every single little date or detail. In academia we typically call this a literature search or review, and it can take up to a month to brush up on a brand new topic.

That’s it for now - Part 2 will go through the next strategy for research training - “First-Hand Experience”. To the next deadline/mini-emergency!

Jack.