Your People

The transformation from “consumer of information” to “creator of knowledge” is a rare and unlikely process.

Research training, especially for students who have never had any prior research experience, is a particularly jarring learning process. This is Part 3 in this blog series on different strategies to develop some skills and “early wins” in research training. Part 1 discussed the idea of information overload, literature searches, and data management, and Part 2 talked about the concept of research design. Today let’s talk about the ever elusive topic of research supervision and mentorship.

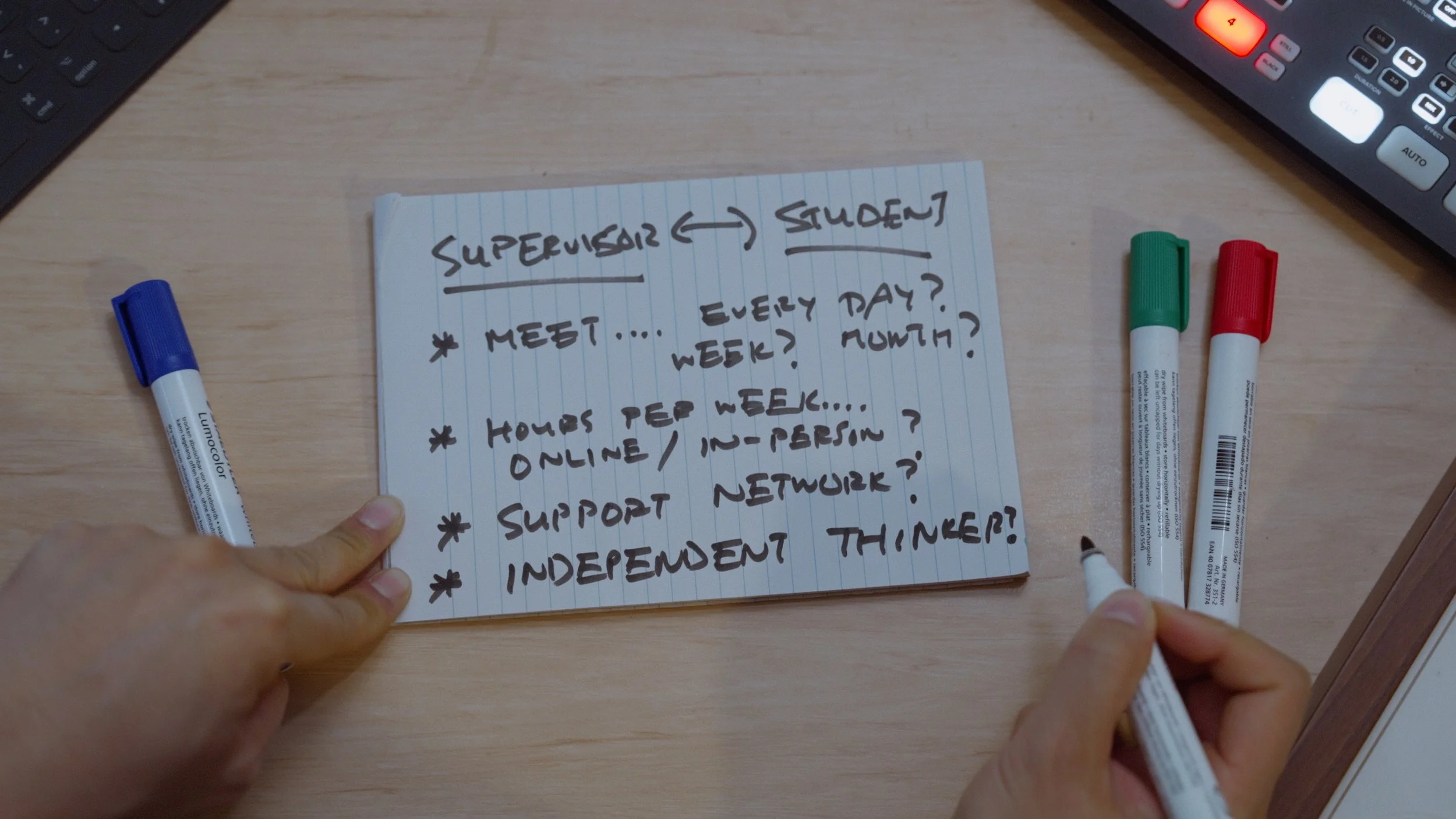

Exactly what should you expect from your supervisor, and what should they expect from you?

Finding your tribe.

Or finding your people, a support network to help you as you slowly develop higher-order research skills. In most universities or colleges you need to have an official supervisor or mentor before starting any research, and they may very well be the first and most important professional connection in your entire career. They have navigated this transition from novice to seasoned veteran again and again, but it may not be obvious how you’re able to access all of their wisdom. This is less of a research or intellectual problem, but more of a human resources problem.

How often do you need to sit down with your mentor?

Is it productive to meet them every week?

Will you have made enough progress in that time?

Does your supervisor even have the time and bandwidth for regular meetings?

Are you making the most of your supervisor meetings?

This is where I see a lot of mentoring relationships go wrong. When the supervisor is too helpful at the beginning, walking through everything and anything, always on-call 24-7. This sets up an unrealistic expectation of what “good supervision” looks like. While it may not be as trivial as “spoon-feeding” (to me a negative “myth” perpetuated about too many students), it doesn’t bode well for your development if you are paralysed by uncertainty and indecision whenever your supervisor is not around.

The best supervisors will be sought after by everyone - their time with you will eventually run out.

Hopefully you found your research supervisor at least in part because of the quality of their work. How high-profile it is, how much impact it has across different sectors. If they keep doing their jobs in the right way, they should be given more and more things to look after, initiatives to manage, opportunities for leadership. Under this model of their career trajectory, they will be needed elsewhere more and more as your project continues under their supervision. Your meetings may become less frequent, the time you have with them will become more sparse.

So… what happens then?

Have they equipped you with the skills to manage your own research?

Have you just been doing what they’ve been telling you to do?

Do you feel confident (or empowered) to make your own decisions in the context of the research?

It takes a Village

Your tribe or support network can’t just be your supervisor - you need to talk to other students, other early career researchers (maybe even other people’s supervisors (!)). Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development suggests that for certain types of learning you may gain more from your peers, who not that long ago just figured out the solution to the exact problem you’re facing right now. Your supervisor may be too removed from these problems to be as relatable or helpful in that moment, and it may not be a good use of the limited time you have with them in your weekly/fortnightly/monthly meetings anyway.

You should recognise the importance of connecting with your peers as part of your research training and take strategic steps to broaden your network right from the beginning of your career. Is there anything you can help others with? What value do you have as part of other people’s support network? All of these soft skills are not discussed often enough as a part of the research enterprise, and we need to recognise their value if they’re to be better integrated into career development.

That’s it for now - next time let’s talk about the thorniest topic of all: “Impostor Syndrome”.

Jack.